Let me tell you about a globalised world, driven by profit, overpopulated, in constant economic crisis, and battered by natural disasters, suddenly devastated by a mysterious disease coming from Asia and quickly spreading worldwide. You might think this to be a fitting picture for the year 2020. However, what I just described was the harsh reality of 1347 CE, when the bubonic plague, or “Black Death” as it was later called, infected the then known world, killing millions and leaving almost no place untouched between 1346 and 1353 CE.

The Islamic world was hit heavily by the plague, and contemporary writers have left us extremely touching accounts describing the horror of facing an almost invincible enemy. Beyond written sources, objects also tell us about the history of this pandemic. The Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) has several objects in its collection that remind us of this sad period of history

The plague travelled from the Eurasian Steppe to the Mediterranean Basin along the same overland and sea routes that formed the backbone of a thriving international trade system connecting East Asia to West Europe. Ironically, these were the same routes through which medical knowledge travelled. For example, apothecary jars such as albarelli[1] reached Italy in the 12th century CE from Syria. Produced first in Syria and Iran and used to store ointments and dry herbs, albarelli progressively became a familiar presence in European pharmacies. A rare Mamluk albarello made in Damascus around 1400-1425 CE (fig. 1) bears the coat of arms of the Medici family, who ruled over Florence approximately 50 years after the city battled against the plague.

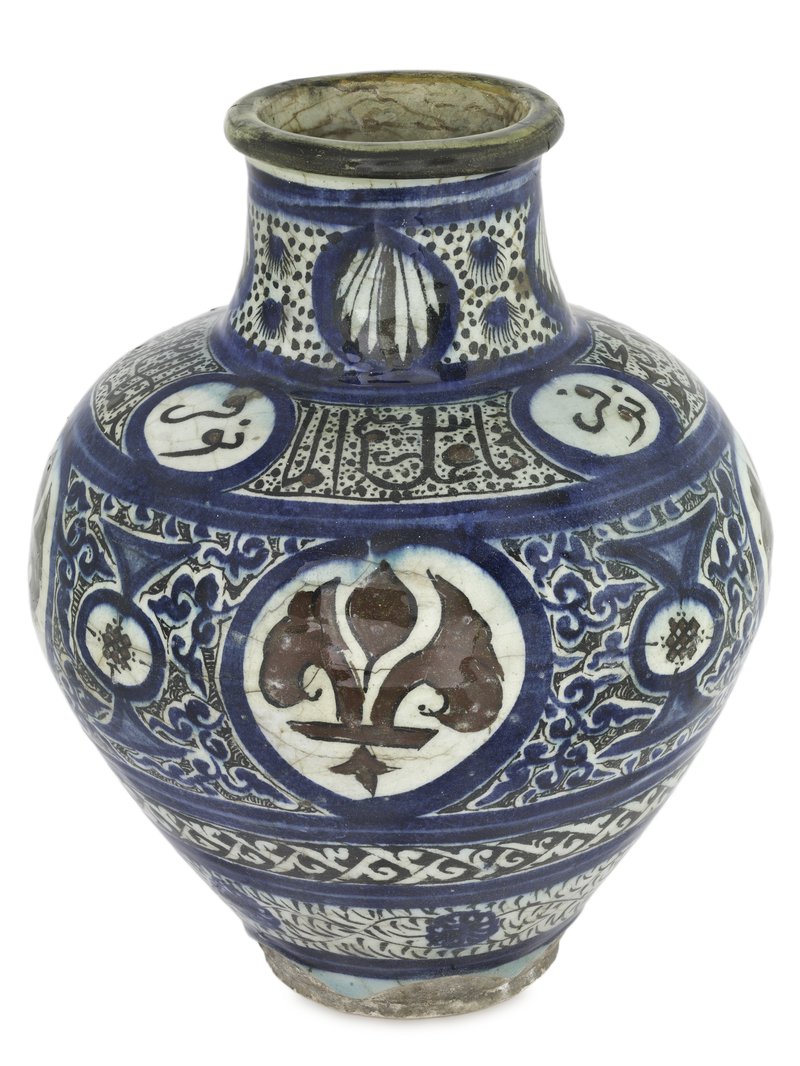

Large cities offered dramatic images of the unstoppable power of the plague. The traveller Ibn Battuta left us a moving account of Damascus, which he visited on his way back to Morocco in the winter of 1348 CE. We can imagine how the major hospitals in the city must have been swamped with patients, such as the Bimaristan al-Nuri, founded in the 12th century CE and still standing today. Today in the MIA collection (fig. 2), a large jar was explicitly made for this hospital. It would originally have contained nawfar[2], a kind of lily used to treat nervous breakdown, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms that many experienced during these months of isolation and social distancing.

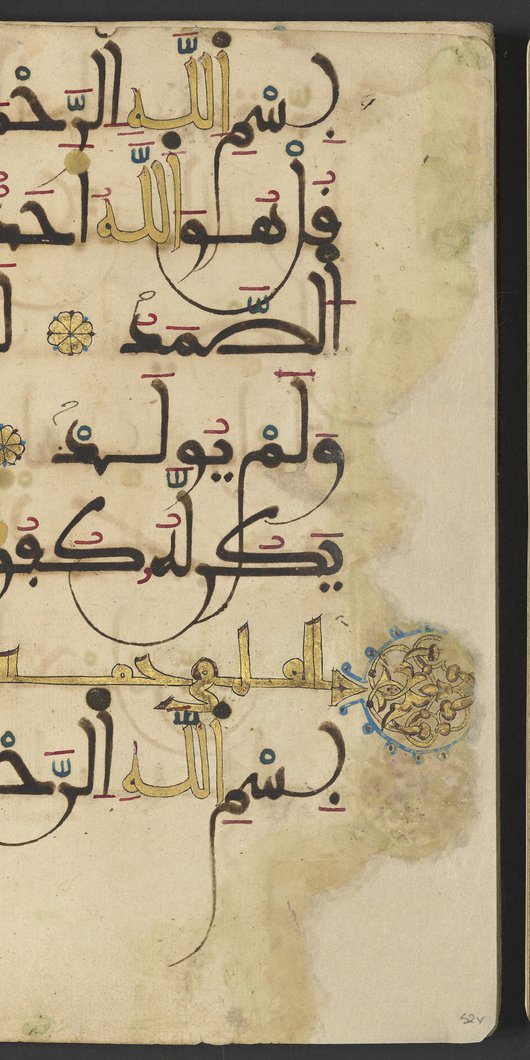

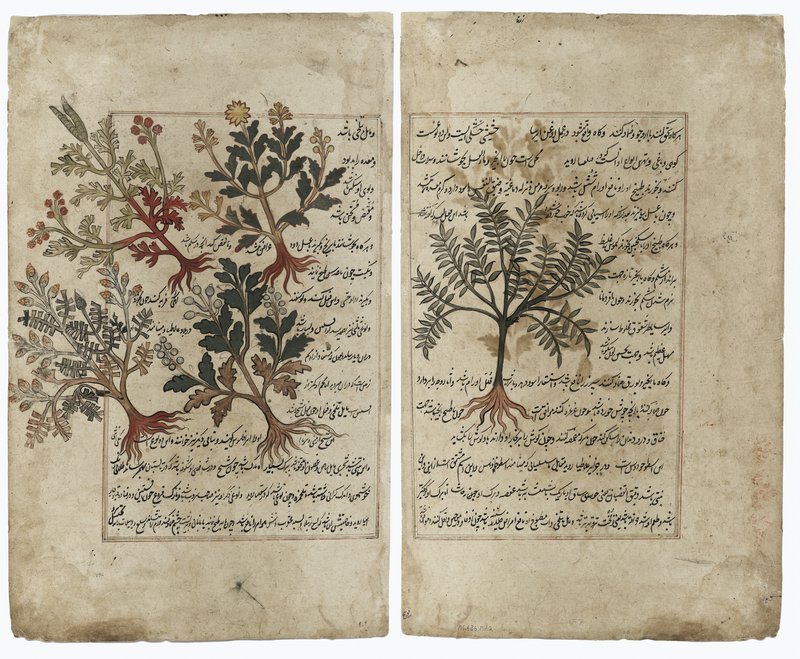

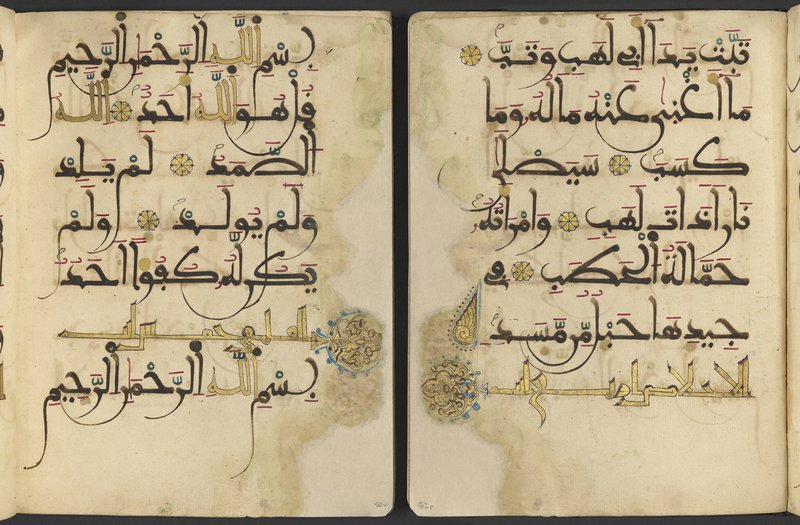

Mediaeval physicians were ill-equipped to fight against a disease whose origins were unknown until 500 years later. Medicine was, in fact, mainly based on herbs, food regimens, and bloodletting, with most remedies drawn from Hellenistic pharmacopoeia such as the popular Dioscorides’s herbarium De Materia Medica[3] (fig. 3). Many people believed that the plague was sent as a punishment by God or came from an evil jinn and turned to magic to find comfort amidst death. Magical beliefs and practices were widespread in urban and rural areas, and various items were used, such as inscribed amulets or magic bowls for concoctions (fig. 4), to provide protection. But in those challenging times, the best companion of all remained the Qur’an; its reading was highly recommended to calm and lift the spirit, with specific verses or surah, such as Surah al-Ikhlas (fig. 5), considered particularly effective against the plague when recited aloud.

Although in the 21st century, we are more prepared to respond to new pandemics, recent experiences have shown the cracks in our hyper-connected, technology-driven world, exposing once again the frailty of human life in the face of nature. Looking back at the past remains a meaningful exercise. As we read about the people who fought and survived the Black Death, their voices and deeds teach us about human ingenuity and humanity’s endless resilience against all odds.

May, 2020

[1] Originally a medicinal jar designed to hold apothecaries' ointments and dry drugs. The development of this type of pharmacy jar had its roots in the Middle East during the time of the Islamic conquests.

[2] The lotus or water-lily flower.

[3] Is a five-volume pharmacopoeia on medical plants and medicines, written between 50 and 70 CE.